Duncan Dewar, the fourth child of Argyll Gamekeeper Donald Dewar and his wife Janet MacCallum, grew up in rural Argyll, in Glassary parish.

In September 1869 he married Margaret Leitch, a labourer’s daughter from Dunoon, in Dunoon and Kilmun, Argyll. She was already expecting the first of their ten children: Donald was born in December that year in Innellan. By April 1871 the three of them were living at Craiginewer Cottage, Low Road in the hamlet of Innellan. Innellan was so small as to not warrant a mention in the extract of John Bartholomew’s Gazetteer of the British Isles, 1887in the parish Genuki entry for Dunoon and Kilmun.

There weren’t just three of them for long: Neil (c1873), Margaret (1873), Janet (c1876) Anne (c1878), Duncan (c1880) had arrived before the 1881 census. The remaining children were Christine (c1882), Peter (c1884), Mary (1886) and Dugald (1887); all were born in Innellan. Duncan was a mason and things must have been tight with 10 children. However things got worse for his wife and children after Duncan died of TB on 3rd November 1890 in the Dunoon area, aged only 47, after both his legs had been amputated.

Poor Margaret, a widow at 41 with ten children, that loss was followed the following year by the loss of her son Neil. Although she saw her daughter Margaret marry in 1892, she herself died the following year, also of TB, on 2nd December 1893 aged just 43.

Her eldest son Donald was working locally by 1891 as a Baker’s Vanman, but he too died young, in October 1900, of TB and Bright’s Disease.

Oldest daughter Margaret, prior to her marriage to James Graham, had been working in April 1891 aged 18 as an nurse, the servant of John Irving, Minister. James was a baker from Greenock. Together they had 3 children although five were listed in the 1901 census so from the timings it looks like James, who was 10 years older than her, had been married before and the first two were from a previous marriage. By 1901 the family of 7 were living in Greenock, the other side of the Clyde from Dunoon.

Her sister Janet married too, and her husband William Tait was a Glaswegian spirits salesman. She had been working in Govan, Glasgow, as a domestic servant by 1891 and they married in the Dunoon registration district in 1895 before having their first son George there. They were living back in Govan, though, in 1898 when son William was born, and for the censuses of 1901 and 1911.

Duncan and Margaret’s third daughter, Anne, stayed in the local area. By the 31st March 1901 census she had married John McKellar, a fisherman/seaman from Kilfinan in Argyll and they were still living in Dunoon in April 1911.

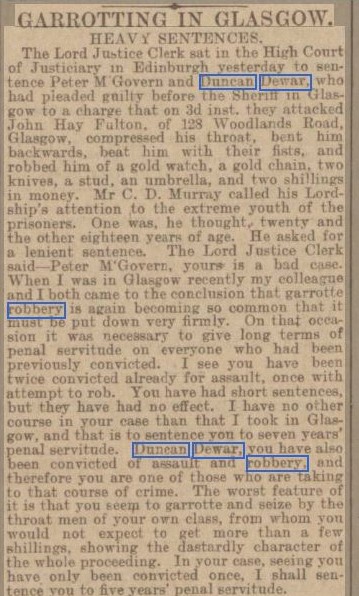

It seems Annie’s younger brother Duncan was the black sheep of the family. He was only 10 when his father died and 13 when he was orphaned. By the age of 18 he was a general labourer but in prison, shockingly convicted at Edinburgh Court of robbery with violence and sent to HM General Convict Prison in Peterhead. This is the story as reported in the Dundee Courier on 17 June 1898,

He was still there in March 1901 for the census, but was released on 16th December that year, ahead of his intended release date of 15 June 1903. Perhaps he decided to start over as on 29th September 1911 he set sail on the Numidan for Boston, USA. However by 1915 he was back and married with a new name, and was fighting for his country in the First World War.

The next of Duncan and Margaret’s ten children was Christine. By the age of 19 she was also in service. She was working as a general servant of Archibald Hood, a Lecturer on Education, and his wife Mary in Kelvingrove, Glasgow. She married John Murdoch Morrison, her cousin germaine (first cousin), in Clydebank in June 1908. John was the Lanarkshire-born son of her Aunt Joan(a), her father’s younger sister; he was a joiner.

Peter was the next sibling; he was born c1884 and only 6 when his father died and 9 when his mother died. I don’t know who he was with or where for the 1891 or 1901 censuses but in August 1907 when he married Annie Lloyd (a farmer’s daughter working as a domestic servant) in Clydebank he was a ship caulker (apprentice). Within a few months he was a dad when Duncan was born in April 1908. Like his brother Duncan he emigrated, unlike Duncan he didn’t come back, dying in Victoria, Australia and being buried in Coburg Pine Ridge Cemetery in April 1914.

Ninth child of ten, Mary, also ended up in Glasgow, she was working as a dairymaid in Pollokshaws, Renfrewshire by the age of 21. She married a Grocer’s Assistant called Alexander Cameron and together they had two sons.

Tenth and final child of Duncan and Margaret, Dugald was born in late 1887 and was an orphan by the age of six. Dugald was luckier than his wayward brother Duncan: he was found living with his wealthy paddle steamer captain Uncle Peter Dewar and Aunt Mary in 1901 in Dunoon when he was 13. He married Catherine Smith in 1910 and things were looking good. However The Scotsman reported on 3rd September 1913 that “Dugald Dewar, carpenter, while working in Messrs Russell & Co.s Kingston Yard, Port Glasgow, fell from the bridge deck to the bottom of the vessel, a depth of about 40 feet. His thigh was fractured, and he was otherwise injured about the head and body. He was conveyed to Broadstone Hospital.”[1]

He died on 5th September in Broadstone Hospital. Catherine who was pregnant with their only son, named him after his father when he was born in March 1914 in Port Glasgow. In 1917 the grieving Catherine took out an In Memorium in the Port Glasgow Express[2]:

DEWAR – In loving memory of my dear husband, Piper Dugald Leitch Dewar, who died at Broadstone Hospital, Port Glasgow, on 5th September 1913.

However long my life may last,

Whatever land I view

Whatever joys or cares be mine,

I will remember thee.

Inserted by his sorrowing Wife and Son, 14 Chapelton Street, Port Glasgow.

Also, in loving memory of my dear cousin, Lance Corporal Neil McLean, who died of wounds on 5th September 1916.

One of the dearest, one of the best,

God in His mercy took him to rest.

This young family of Dewar children had such a hard time of it, losing their parents young and being (by various means) being sprinkled round either side of the Clyde. I found them witnessing each other’s marriages when thigs had settled a bit – I’m so glad they could stay in touch.

[1] The Scotsman 03 September 1913, P6, col 4

[2] Port-Glasgow Express 05 September 1917, P2, Col 2, In Memorium